Investigation Statement

To investigate cultural appropriation of Tā Moko in Aotearoa’s tattoo industry, and how the designs and processes are the right of Māori.

To investigate cultural appropriation of Tā Moko in Aotearoa’s tattoo industry, and how the designs and processes are the right of Māori.

Wai262 claim is a claim to restore and enhance Te Ao Mauri. Wai262 directly relates to Whakapapa and Tino Rangatiratanga and how from whakapapa, comes the rights and responsibilities of “Tangata Whenua- people of the land.” Which is a way of existing to tikanga, customs and laws. Wai262 is a claim to the authority of Tino Rangatiratanga which is guarentee’d under Te Triti o Waitangi, which is central to the mauri of Māori culture, Reo, Matauranga and identity of Whanau, Hapu and Iwi. This relates to my topic as Moko is deeply representative to your whakapapa and needs to be reclaimed as such, instead of just a piece of body art ( Kirituhi.)

In evidence given for the Wai262 claim, Mrs Del Wihongi (Hema-Nui-a-Tawhaki Whihongi) said “I wish to explain the holistic relationship between the cosmos of the universe, the gods, the plants, animals and māori. This relationship discribes the rights and responsibilities maori have to the other partners within this relationship. This relationship is particularly important to our customary practices and norms.” and also by Mrs Saana Murray, “Māori control over things Māori”. These statements are important to one of my case studies of pākehā using moko which is genetically a māori right, and one that should be preserved and respected in Māori culture for it’s relationship with whakapapa, ancestory and whanau, and all indigenous flora and fauna.

https://www.waitangitribunal.govt.nz/news/ko-aotearoa-tenei-report-on-the-wai-262-claim-released/

Purpose of the moko:

Cerimonal Process of the Moko

Right to Recieve a Moko Tattoo:

When it’s not okay:

Changes in Tikanga surrounding Tā Moko:

Moko vs Kirituhi : Moko = whakapapa, Kirituhi= Skin Art.

Avoidance of Harm: Potentials of physical or phycological harm for participants resulting from the investigation? No. For me conducting the investigation?

Benefit : What benefits can your investigation have for participants? Learn more about indigenous culture of Aotearoa and it’s traditions. Their communities? How to avoid appropriation and understand the different rights to culture that the māori have, and to the māori community to reclaim their culture. You? To learn and engage in a culture that I have been sheltered from for most of my life and reconnect with my country.

Justice: To what extent will the benefits and burdens of the research be fairly distributed? Mostly be fact based regardless and backed up by treaty claims and the investigation analysis I have learned.

Kaua e Takahia te Mana o te Tangata : How will the investigation feedback to the participants/communities involved? Openly challenge the thought of cultural appropriation and how cultures can emerse and connect.

He kanohi kitea : In what ways can you make yourself a familiar face with participants and communities? Talk and be open with people as much as possible. I was writing this at the bar and a Māori Woman saw what I was writing and came up to chat to me about how she feels about pākehā appropriating her culture and her own suggestions of things for me to look up, such as the Sally Anderson Case.

Titiro, Whakarongo… Kōrero : How will you introduce yourself and your investigation in a way that allows you to look and listen before speaking? Understand some people may have been a part of appropriation through their whanau and respectfuly portray my points.

Two of the issues of the treaty that was addressed in this lecture was the dictation of the Pākehā and how it has warped how todays community has addressed and learned about our history and also the blatant racism from the crown that came after the treaty was signed and the drastic affect it’s had on the indigenous people of New Zealand.

These were surprising to me as I have been a Pākehā who has been sheltered from the racism presented in the treaty and it’s reflection on modern day society, from neglection in the education system and my whanau’s background presenting an ill-informed mind set to the treaty I genuinely had no realisation of background white-supremisy in Aoteatoa. This is especially highlighted in the text on pages 3 and 5 where prof. Margaret Mutu writes about the british attitudes towards race and claims, and european civilisation jusitfied stealing land from the indigenous people of Aotearoa by saying their religious, uncivilised and coloured society made them superior and gave them the right to determine another races laws and sociatile manner. And on page 5 she continues with the back up of how māori culture is met with violence, and also with dismissal of integrity. This still carries through today with the treaty claims and how we respond to Māori culture (i.e teaching Te Reo Māori in schools, the hāka, ect.). While things are now being openly discussed – an important step for change and equality- there is still a long way to go in the way we identify and accept our national culture of Māori people.

Another thing that surprised me was how greatly the māori have suffered in terms of government, economical and social support, due to the misinformation and racist views of pākehā.

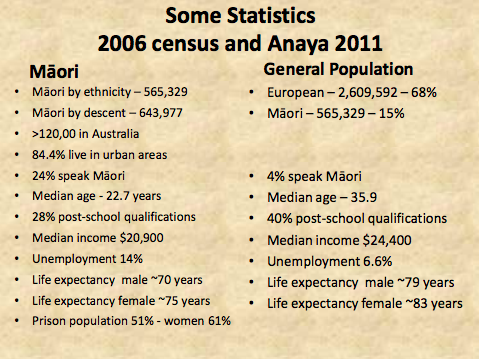

Black and white facts of lower school qualifications, population of Te Reo Māori speakers, incredibly low income, high unemployemt rates, low life expectancy, high prison population, is thrown in your face and it shows how dire their experience with the government and social economy really has been. Colonisation and capitalism has plummeted their ability to grow as a culture and created the misdemeaner of poverty.

It’s helped me to see where Aotearoa’s society has failed our national culture and where we need to step up to bring us back to an equal society.

Te Mata Aho collective, the collaboration of four Māori women to produce large scale textile works that portray the complexity of Māori lives and culture. All four women have post graduate studies in textiles, history and the arts, and their heritage has given them the knowledge and right to share their knowledge with the greater community. They have worked with materials that are relevant and prevalent to the contempory māori experience, which connects a younger generation and is familiar to the māori community, but still honors the history.

The Calypso Sculpture in Maryland was formulated for public engagement to impact on the waste in our oceans, using plastic bags, the public were to tie it on to the pre-framed sculpture. As the sculpture is interactive, it targets the younger community and visitors to the aquarium (families) to contemplate and think about what was needed to help the earth and endangered species.

In my own project, the communities I am targeting is the tattoo artist and collectors, some of who are indiginous, however many would be artists and collecters who struggle with the challenge of putting the line through art and cultural appropriation. Moko tattoos hold a significant and meaningful process to both artist and the holder, it is said to hold mana and to hold knowlege, so why is the community of the tattoo industry so contempt with the apropriation if they dont have the right to put that on to someone’s body? Ways i could research this/access knowledge to this is:

Te triti worksheet:

Part 3:

One vacant wellington building I thought of is the Museum stand at the basin reserve, a grandstand that was opened in 1925, and forced closure in 2012 due to earthquake risk.

How is it used/ who uses it?

Currently abandoned, recent photos from urban explorers Urbexcentral: “https://urbexcentral.com/” “https://urbexcentral.com/2016/06/03/abandoned-wellington-grandstand/#comments” , suggest that it is being used for storage and for refuge to ‘dynamic’ people.

Social History:

The Basin reserve where the museum grandstand is located was built by prison labour from Te aro gaol in the mid 1800’s and paid for by the wellington cricket community, so in 1866 after drainage and maintanence was completed the basin became the home of cricket for wellington. In 1925 the grandstand was opened for spectators of cricket matches in the basin, and was used as a cricket museum in more recent years, finally closing due to earthquake risk in 2012. It has been left abandoned and holds many valuable trophies and photographs of the buildings history and souls who came through the building, it is still being debated if it will be demolished.

The building’s grand interior and deep history of slavery, racism, capitalism and community shows it has had the purpose of display and curiosity, why could we not strengthen and re- open with a new space to show the impacts of society and the violent history of prison labour that New Zealand brushes over. I would like to see the space utilised to impact the people who come to the basin to remember who gave the cricket community their own space. Educate their community through art and display.

Part 1:

“Rasquache” Culture, decending from working-class Mexico. A Visual culture reflective of a crafting and repurposing aesthetic. Also associated with shared heritage and sustainability, done effectively through economic pressures and hardships.

Economic and political hardship provides the raw materials for the visual aesthetic and to be repurposed, and it also allows for value of creativity over regularity. “mocks the border” of the social tier groups.

While it is a culture thats origins are distant from New Zealand, my mind drifts to the Cuba Street culture of Wellington, and how the rough-housing community have their own flare for repurposing and some weaving, drawing on boxes, making music and body art are reflective of a path of generations who have gone in many different directions, but kept the Rasquache culture alive.

You don’t have to look far to see the protesters and people fighting for change through street art and creative statements. Rasquche culture has travelled far and may have been altered to fit our own communities, but its values of community, rawness, originality, political and social challenge has remained the same, but adapted and evolved into a movement around the world.

In the interview with Lee, he brought up points which showed why it was a hard but rich history of New Zealand and one that really reflected the attitude of other communities towards the Homosexual (LGBTQ+ came much later) communities in the 70’s.

Notes:

Two topics that interest me or I found while searching spaces/ interests:

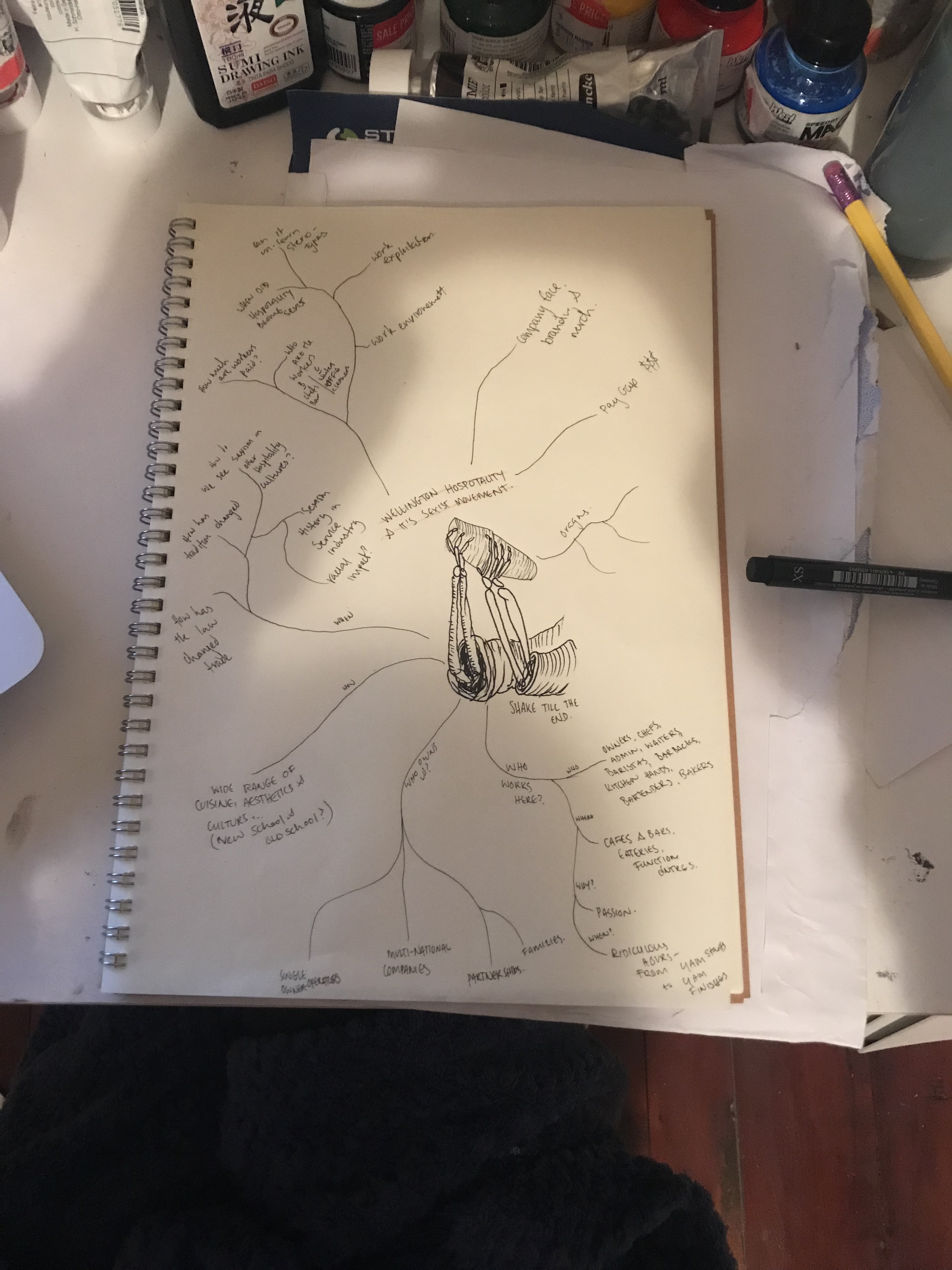

See attached mind maps: